Thoughts on Jennifer Lawrence and Settler Colonialism in Hawai’i

Recently, a video of actress Jennifer Lawrence’s appearance on Graham Norton’s talk show went viral. In the clip, she talks about filming the second Hunger Games movie in Hawai‘i, and tells what she seems to think is an amusing story about how she used rocks considered sacred by indigenous Hawaiians to scratch her butt, stating flippantly, “I dunno, they were ancestors, who knows — they were sacred.” Many locals to Hawai‘i, and others, were understandably not amused.

In an article published on the Guardian’s website shortly after the release of this video titled “Jennifer Lawrence, please keep your butt off our ancestors,” Hawaiian scholar J. Kēhaulani Kauanui explains why Lawrence’s behavior and telling of this story is so harmful – not only is her choice to ignore that which is sacred to the indigenous people of Hawai‘i disrespectful, but it is a part of a legacy of mocking Hawaiian spiritual beliefs that then serves to justify the continuation of U.S. imperialism in Hawai‘i. Kauanui quotes Lisa Kahaleole Hall, who states that “by making Hawaiianness seem ridiculous, kitsch functions to undermine sovereignty struggles in a very fundamental way. A culture without dignity cannot be conceived of as having sovereign rights, and the repeated marketing of kitsch Hawaiian-ness leads to non-Hawaiians’ misunderstanding and degradation of Hawaiian culture and history.” As Kauanui and Hall argue, then, far from being a harmless joke or misunderstanding, Lawrence’s behavior directly participates in the continued devaluation of Hawaiian culture that has been central to settler colonialism in Hawai‘i.

Lawrence’s story, and Kauanui’s article, also made me think about how Hawai‘i has been, and often still is, portrayed to mainlanders as a paradise available to us for our enjoyment and use. In her work on U.S. hula circuits during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Adria L. Imada discusses the construction of this “‘imagined intimacy’ between the United States and Hawai‘i, a potent fantasy that enabled Americans to possess their island colony physically and figuratively” (11). Recently, looking through old issues of Life magazine for another project, I was struck by the ways I saw these imagined intimacies at work. Particularly in the years directly before and after Hawai‘i’s statehood, articles and advertisements alike focus on the islands’ beauty, portrayed local people as exotic, yet in many instances desperate to be American, and often feature white mainlanders pictured smiling, relaxed and wearing leis with the beach and Diamond Head looming behind them. (An example of some of the photographs published in the magazine can be found here – http://time.com/3739614/hawaii-before-statehood-color-photos-1959/). This perception of Hawai‘i as a paradise, the land of aloha and welcoming, persists as the overwhelming narrative of the islands today. When I returned to living on the mainland after living in Hawai‘i for three years while working on my Master’s, I found that most of my fellow mainlanders’ responses to finding out I had lived there drew on these images, marveling at the thought of living in paradise and wondering if it’s really as amazing and perfect as they think it is. Alternatively, many asked whether I experienced “reverse racism,” stating, “I heard they hate white people there.” Nearly all responses I got to the knowledge that I had lived in Hawai‘i fell into one of these two categories, leaving little room for nuance in a discussion of what is like living in any place, and emphasizing the extent to which Hawai‘i as a place is still so much seen as an exotic “other” to the U.S. mainland.

To me, both Lawrence’s behavior and the questions from my fellow mainlanders about living in Hawai‘i exist in direct relation to the way Hawai‘i has been constructed as a place is the imperial imagination of the United States. Lawrence’s story relies both on the devaluing of Hawaiian spirituality and belief as ridiculous and not real, and on the idea that Hawai‘i is a place that is available to her to have fun and do what she wants without consequence. Uncritical questions from mainlanders about Hawai‘i as paradise, or on the other end of the spectrum, Hawai‘i as a place that unilaterally hates white people, also depend on the idea that settlers have the right to that space – it’s our paradise, where we can and should be welcomed with aloha. If we’re not, the imperial fantasy is disturbed, and the explanation becomes about what is seen as unfair anti-haole sentiment rather than a conversation about the persistent effects of settler colonialism.

Works Cited

Imada, Adria L. Aloha America: Hula Circuits Through the U.S. Empire. Duke UP, 2012.

The Margazhi Music Festival and the Need to Challenge Home-Grown Cultural Imperialism

In December every year, Chennai (a city in the South-East of India) hosts ‘The Margazhi Music and Dance Festival’, one of the biggest performance arts festivals in the world. A plethora of India classical musicians and dancers perform at various venues across the city, usually between December 15 till January 15 (during the Tamil month of ‘Margazhi’), although these days the performances begin early on in December and extend all the way till the first week of February. The festival predominantly features performances by artists who belong to upper castes (usually belonging to the Brahmin community) in concert halls (referred to as ‘sabhas’ in Tamil) mostly run by elite Brahmins in the city. Needless to say, the audience for these performances is primarily comprised of Brahmins. This article – http://thewire.in/86134/madras-music-season/ – which was published yesterday in a renowned digital news portal, traces the origin of the Margazhi festival and suggests that “while the very genesis of the festival lies in the tradition of protest against imperialism [ – it was established as a means of protest against the Christmas and New Year traditions of the British -], it has become a festival of the caste-elites where the presence of the non-Brahmin communities is almost non-existent” (Ramanathan). The author also proposes a need to challenge this home-grown cultural imperialism in order to make the festival more inclusive and accessible to members from other communities and castes.

Here’s a video that contains excerpts from a few concerts held during the Music Season in 2014 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ySnDwlXyG-Y, and here’s the link to the website that lists all the events happening during the festival this year – http://www.chennaidecemberseason.com/.

“Postcolonial Pop”: Music and Rhetoric

In my own life, I’ll often listen to angsty music that suits a particular mood. (Annoyed by politics? Maybe I’ll play “American Idiot” by Green Day or “Dear Mr. President” by Pink. Societal issues getting me down? I’ll listen to more Green Day, who has a new song out called “Troubled Times.” If my family is the source of anxiety, I might play Pink’s “Family Portrait or You+Me’s “Break the Cycle.” This might’ve been a completely asinine aside, but you get the idea.)

The larger point is that I’ve always believed music can be about so much more than the cliche love songs so many assume to be the rule of thumb. I always admire musicians who use their performances as a form of political advocacy, so I was especially interested when I stumbled across the article “Meet the Desi Artists Fighting Back Against Trump with Punk Rock and ‘Post-Colonial Pop’.” This article profiles several groups and talks to each about how their music is influenced by their own hybridized roots. Below, I’ll summarize and quote from the profiles of the punk groups, and I’ll include the same links that the article did in case anyone wants to listen to the music:

- Doctors and Engineers is a band that morphs the sounds of garage rock with Indian folk music. They look to disrupt stereotypes–and presumably, “Doctors and Engineers” may very well be a name that plays into the model minority stereotype in a rather tongue-in-cheek way. Their lead singer, Sri Panchalam, expressed her anxieties of releasing their first album in the immediate aftermath of the election: as a collective, the band “felt an overwhelming feeling to sit back and absorb the fact that four years of Trump’s government would be opposed to their ‘immigrant kid music’ and support for social justice causes.” Panchalam also admitted to asking herself,”Why is it suddenly dangerous to be who I was, even more dangerous than it was to be before?” But the band performed anyway, and the article interview pointed to the concert as an opportunity for solidarity: many in the audience were from different minority groups. (In this sense, how might the “solidarity” at a concert function? Does it simply act as a collective catharsis, or could the audience realize their common ground and be inspired to organize in more deliberate ways?) https://doctorsandengineers.bandcamp.com/

- The Kominas are described in the article as “Pakistani-American punks.” Islamophobia is a more direct–and personal concern–for the Kominas. A sample from their album Stereotype puts these anxieties into verse: https://kominas.bandcamp.com/track/pigs-are-haram The band also performed shows in the week after the election, and the article noted that these shows offered “safe spaces” in a similar fashion that Doctors and Engineers’ show did for their listeners.

For the featured groups, a common issue seems to be that phobias that affect one group affect all the groups: whether these individuals are Muslim, Sikh, or Hindu, most of the discrimination they face is based on an assumption of a homogeneously harmful brown-skinned “other.” The different ethnic backgrounds are inconsequential for those phobic toward any one of these groups. But in terms of their work as musicians, the notion of a concert as a safe space was particularly intriguing for me. Rather than simply offering lyrics that might resonate with minority listeners, fandom becomes a small-scale means for solidarity. As I noted at the end of the Doctors and Engineers summary, I wonder whether this solidarity can go beyond catharsis. For someone like me, these bands’ songs might force me to share their consciousness for a three-minute spurt; for these musicians, that consciousness of discrimination is far more personal and pervasive than I’m likely to ever know firsthand; sure, I might be afraid of anti-women policies or economic repercussions, but it’s worth hearing out (literally) what these Desi musicians have to say about their own encounters with prejudice. It’s a very small step toward becoming a better ally.

Work Cited

Mustefa, Zab. “Meet the Desi Artists Fighting Back Against Trump with Punk Rock and ‘Post-Colonial Pop'” Noisey. Vice, n.d. Web. 10 Dec. 2016.

Lasting Language

The images and phrases used to demean Dutch TV presenter and politician Sylvana Simons are clearly racist and draw on discourses of slavery and colonialism. These incidents have made the news in the last few weeks because Simons is a rising star in the new political party Denk (Think), and also because ‘tis the season for Zwarte Pieten, the black helpers of Sinterklaas which I mentioned here and of which Simons has been critical.

Our recent class discussions have me reading this news with a few questions related to why certain public figures become the object of hate speech, bigotry, and threats of violence. As I reflect on the Simons case, I can’t help but think that her being a woman is central to the story. The radio producer who mentioned in the BBC article, the one who grunted when talking about her, also told her to be quiet. A song by a prominent cabaret singer circulated about her, suggesting in with an upbeat, light-hearted melody that she leave the country. Rather than serious political challenges, the instigating materials have been these comments and songs that treat her like someone not to be taken seriously.

Related to this situation, the Dutch government has said that it will change some of the language used to describe people of color — language that dates back to the colonial period and to the migration that resulted from it. Rather than identify non-white residents as “allochtoon,” or foreigner, or non-native speaker, the government has proposed finding terms that do not emphasize a person’s supposed origins. After all, even though “allochtoon” has technically meant a Dutch person with one or more parents born outside the Netherlands, its colloquial use has become far broader and is applied to third generation citizens, as well.

Some of the racism affecting Simons and others is enabled by language, and it seems important to make these changes — and equally important that new language not be determined only by the government and dictated in a top-down fashion.

Questions of Liberation?

Considering my research interests combined with coursework from this semester and the current political climate, the question of liberation (political, economic) has been on my mind a lot. Not necessarily questioning whether it is possible but rather, how? What makes liberation movements successful? Historically, liberation has been linked to the nation-state, equating political and economic control of a state space to freedom. However, postcolonial African states have historically had a contentious relationship with the state, with the twenty-first century ushering in a search for more horizontal forms of power through supranational institutions. Mahmood Mamdani (1996) connects much of this to the inherited colonial legacies while Frederick Cooper (2002) argues for the gatekeeper state concept, whereby the politico-economic dysfunction that many African governments suffer from derives from a specific historical order where the extraction and exploitation of resources by colonial powers limited the political foundation of which African territories and future states would be formed. Therefore, the survival of the African colony, and eventually the African state, became dependent upon external resources and support rather than internal factors, which led to a number of issues, including the centralization of political power and the development of authoritarian regimes. Therefore, a number of factors, including dysfunctional colonial legacies, the influence and role of the international economic system, and the centralization of political power have all contributed to the struggle of establishing the state’s political and economic independence in Africa, illustrating the extremely contentious relationship the African state holds with the nation-state. Moreover, these factors have worked together as an interconnected system where dysfunctional neocolonial legacies informed the transition to and adoption of centralized state power.

Therefore, because of the oppressive history of the colonial state, and frankly the structure of the nation-state itself, ideas of liberation are at the heart of twentieth century African history. But, what does it mean to be liberated? Even though the nation-state functions in conjunction with the capitalist system to oppress groups of people, an independent nation-state is often associated to liberation within the framework of political and economic independence and freedom. Many scholars, writers, and poets have touched upon what means it will take to achieve liberation: Frantz Fanon (1961) argues for the lumpen proletariat of Africa to take up violent means because the oppressor only speaks and understands the language of violence; Amilcar Cabral (1979) believes education is key in the liberation movement. However, despite the plethora of rich material surrounding tactics for liberation, few write about the post-liberation period – what happens after the armed struggle to maintain liberation? To a certain extent, this seems to be a key question facing postcolonial states that have supposedly “achieved” liberation vis–à–vis a politically independent nation-state.

In his article “Girls with Guns: Narrating the Experience of War of FRELIMO’s ‘Female Detachment’” (2000), Harry G. West illustrates an example of limitations to liberation. West begins his article with a discussion of child soldiers, discussing the ways in which they are often used, through media accounts, to “sensationalize and exoticize” Africa, speaking to the ways in which a Western understanding of ‘youth’ often limits our understanding of “the youth” and therefore, who qualifies as a child soldier. However, in his understanding of child soldiers, West re-centers the discussion to focus less on the question of the reintegration process and more on the question of “why?” He explains how, increasingly, literature published on child soldiers pushes further and further into this idea of reintegration: how should child soldier reintegrate into society? How can NGOs and other institutions help facilitate this process? Many contributors and scholars in this field often argue that the healing of trauma from war is connected to the reintegration process and the reestablishment of social networks. Pushing against the idea that reintegration is equivalent to an answer, West argues that the narratives from this research suggest “the need to refine our understanding of how ideology frames the experience of young people at war.” (182) Moving beyond the introduction, West then uses the articles to specifically showcase the experience of young women and girls involved with FRELIMO.

West concludes that rather than focus on this question of reintegration, we should be focusing on the disappointment. He argues that, based on his research, many “were less traumatized by wartime experience than they were by the post-war unraveling of the narrative that had made sense of that experience of the time.” (191) So, in reality, it is not the process of reintegration or the experience of the war that is causing trauma, but the failures of the liberation struggle to meet its promises once the guns are put down. Therefore, this article highlights how oftentimes, the liberation movement never thinks beyond the armed revolution, typically resulting in the revolutionaries reinstituting and adopting the inherited colonial legacies. While it is important to discuss and envision the armed struggle, it is also crucial for the liberation movement to think and imagine beyond the struggle to understand how foundational ideological cornerstones of the movement will be implemented and executed in a post-liberation society. Without articulating the vision for the post-liberation society, a liberation movement is bound to fail and, in the case of Africa, fall back on inherited colonial legacies and authoritarian politics that characterize much of the oppression in the first place. The frustration presented by constantly envisioning liberation through the nation-state with little attention paid to the structure of the post-liberation society begs for alternative notions of liberation — alternatives that I don’t necessarily have an answer for but am hoping to interrogate in my research in the future.

(Delayed) Reflection on the Election

The aftermath of this election has been characterized by a number of failures, most notably the way in which folks have organized around the sentiment that the Democrats failed the American people. When Sanders first announced his candidacy, folks understood it as at least Clinton would have an opponent to help prepare her for the “real debates” in the fall. However, the massive support for Sanders is not something that the Democratic Party calculated and the establishment did everything they could to continue to propagate support for Clinton as, just as in 2008, this was “her year”. And while the final platform that Clinton ran on was touted as the most progressive platform of any Democratic candidate in recent history, it was only done so as a way to capture the votes of Sanders and other third-party voters, all denying the history the Democratic Party has of oppressing, exploiting, and violently assaulting communities of color, most notably the Black community. It seems that the Democrats failed the American people on a number of levels in this election.

Considering the emails as, what I understand to be the least of her problems (not to downplay their significance for the general american public but they essentially just validated people’s feelings not only about her but the Democratic Party at large), one need to look no farther than Columbus establishment politics to see how the Democrats decided, without listening to the people at large, who the nominee was going to be (not necessarily a critique of Clinton, but of the party more largely speaking). First and foremost, the Democrats don’t (and haven’t for a while) worked for the working class. While the final platform that Clinton ran on was, of course, the most progressive platform of a Democratic candidate in recent history, it only was so because Sanders and his supporters, as well as a strong, vocal presence of third party opponents, that pushed her to the left. It should come as no surprise that some of the states she struggled to win in the final election are states that Bernie had overwhelming support in during the primaries (looking at you Michigan). But I think the effort was too little too late to capture the attention of working class white America.

Secondly, capitalism is failing us on a global level and the rise of very conservative right wingers only further supports this. To substantiate this claim, the IMF came out and said that neoliberalism (and the frightening austerity measures it imposes on society) actually isn’t working for folks (surprise!) and is, in fact, causing greater economic and social inequalities. To again bring this point back to the working class, America is one of the only “industrialized” countries that doesn’t have a labor party as a political faction. While a significant amount of speculation, analysis, and writing has been conducted on this topic, I would argue that this is most prominently due to the historical differences in the rise of the Right (simultaneously resulting in the suppression of the Left) and how America learned to prioritize race over class – the disastrous effects of Bacon’s Rebellion – meaning that racial solidarity will always be first for white folks.

Which brings me to my final point and that’s whiteness. White women overwhelmingly (53% last I read) supported a misogynistic, racist, homophobic, islamaphobic candidate. Now there is the obvious overt racist category of folks, but there are also folks who are not overtly racist, may even consider themselves an ally of any of the aforementioned communities, and still (white men and women alike) thought “hey, this dude is fine for president.” This is all to say that at the end of the day, I’m not very interested in how the Democratic Party reacts, because I think they, as a Party, have been riding President Obama’s coat tails for too long and, in doing so, have failed to provide concrete, meaningful material economic and social change. Therefore, what I’m most interested in is how the very disgruntled, ready to fight left will rise. I say all of this not as a response to further vilify Clinton because continuously making a single person the enemy is a waste of time as it belittles the larger, systematic problem which, in this case, is the establishment politics of the Democrats.

(Speaking to this same point about not focusing on an individual for fear of missing the systematic issues, Jacobin published an interesting piece regarding the Conservative Movement and not writing Trump off as an anomaly: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/08/donald-trump-president-khizr-khan-joseph-mccarthy/)

“They never gave back/They only took away” : Serafina’s Promise and the Tonton Macoutes

Ann E. Burg’s Serafina’s Promise (2013) was the only other novel on Haiti that I had read before we read The Dew Breaker (Edwidge Danticat, 2004) for class last week. Burg’s verse novel tells the story of the young 11-year-old Haitian girl, Serafina who struggles with poverty, and yearns to go to school so she can become a doctor. During our discussion of The Dew Breaker in class last week, we mulled over the categorization of the characters in the novel into Elite Haitians, Subalterns and State Actors. Unlike the rich and elite Gabrielle Fontaneau, or the privileged Ka and Aline from Danticat’s novel, Serafina’s Promise revolves around the child-subaltern, who “sweep[s] the floor and empt[ies] the chamber pots” every morning and “pile[s] charcoal to make the cooking fire” at night to “work hard and help [her] Manman” in the hope that her mother’s unborn child would survive at least this time around (Burg 2). At the beginning of her novel, Burg characterizes her protagonist as a helpless, young child “wish[ing] [she] could/ jump rope and laugh/ with [her] friends”, “Julie Maria and Nadia”, who, in Serafina’s words, are as “playful as children” ought to be (3).

Burg positions this child as an outcast by virtue of her positionality as a young girl from a poverty-ridden household in Haiti. She holds her desire to become a doctor, as a secret, close to her heart, and she knows that in order “to be a doctor,/ [she] must go to school” (Burg 9). “How will I ever go to school/ if I must always help Manman?”, she asks (Burg 9). Serafina is deprived of her rights as a child because of the responsibility that has been forced down on her by her family. While her Papa recognizes that Serafina “[has] a gift”, when she helps care for her mother’s blistered skin, “[a]ll [her] Manman wants [her] to do is work” (Burg 25). Papa recognizes that “[Serafina’s] still a child”, but “Manman argues” that “[s]he’s eleven years old” and that her daughter needs to attend to her chores (Burg 27).

Burg’s novel, similar to that by Danticat, also features mentions of the Tonton Macaoutes, of which the ‘Dew Breaker’ is also part. Serafina’s beloved grandmother (Gogo) has nightmares of the Tonton Macoutes, “waving their long,/ heavy machetes”; with “their straw hats and dark glasses,/their blue shirts and belts made of guns/and bullets [. . . .] demanding that [they] leave [their] land” (Burg 32). On Flag Day, when Serafina — who has been struggling to find out how her grandfather (Granpe) died — asks Gogo to tell her the story of his death because “[she is] old enough to know”, her grandmother recounts the tale of her husband, who “taught himself to read” and believed that “[e]ducation [was] the road to freedom” (Burg 28-30). The Tonton Macoutes “suddenly appeared in [their] front yard”, Gogo says, and she goes on to narrate how they grabbed Granpe and took him away from them forever.

While Beatrice in Danticat’s “The Bridal Seamstress” tells her interviewer that they called the torturers “shouket laroze” (Dew Breaker) because they would “[o]ften [. . .] come before dawn, as the dew was settling on the leaves, and [. . .] take [victims] away,” (131) Nadia, Serafina’s friend, compares them to “evil bogeymen”, who were given power by “[t]he president and his son [ . . .] to destroy anyone/who didn’t agree with them” (Burg 33). When Serafina asks Manman about the Tonton Macoutes, her mother says that “[t]hey are shadows now” and that “Nadia should not even speak of them/Neither should [Serafina]” (Burg 33).

Burg’s novel, told in first person verse, is a fantastic way to introduce the history and culture of Haiti to upper elementary level children. It even references the catastrophic earthquake that struck Haiti in 2010, and contains a liberal dose of Creole phrases and a “Haitian Creole Alphabet and Pronunciation Guide” and a “Glossary of Foreign Phrases” towards the end of the book (Burg 296-7). I highly recommend this verse novel, which, due to its format, would appeal both to “struggling” and “achieving” readers.

Works Cited

Burg, Ann. E. Serafina’s Promise. New York: Scholastic Press, 2013. Print.

Danticat, Edwidge. The Dew Breaker. New York: Vintage Contemporaries, 2004. Print.

Reflections on Fathers in The Dew Breaker

In The Dew Breaker, the role of fathers is quite important to the development of the several of the stories – the Dew Breaker is introduced through the lens of his daughter and her relationship to him long before we learn any of the details of his past life, in “Monkey Tails,” Michel’s fatherless childhood and his own impending fatherhood shape the narrative, and the funeral singer’s story tells of how she became a funeral singer because of the loss of her father, to offer just a few examples. In “Monkey Tails,” Michel provides a line that, for me, in many ways encapsulates why fathers are so important to the stories told throughout the book, stating that he is “part of a generation of mostly fatherless boys, though some of our fathers were still living, even if somewhere else – in the provinces, in another country, or across the alley not acknowledging us. A great many of our fathers had also died in the dictatorship’s prisons, and others had abandoned us altogether to serve the regime” (141). In relationship to the significance of fathers throughout the book, I am interested in looking at two of the representations of father figures: The Dew Breaker and his daughter, and the mention of the president as “father.”

Ka’s relationship with her father, the Dew Breaker, in many ways provides a frame for the other stories in the book, as the story of her learning her father’s true past figures into both the beginning and the end of the book. The sculpture of her father, in which Gabrielle Fonteneau recognizes her own father, prompting Ka to note that she may have inadvertently stumbled into the “universal world of fathers,” provides a container for how Ka sees the Dew Breaker and the extent to which her view of him depends on his having been a prisoner, his past life having been a humble and difficult one (12). Danticat introduces Ka and her relationship with her father at the moment that relationship changes, due to the revelation that her father was not, in fact, a prisoner, but rather someone who worked in the prison, torturing and killing prisoners. Although we quickly come to learn that Ka’s relationship with her father seems to be a close one – in “The Book of Miracles,” Anne is in some ways a third wheel to their relationship – the opening line of “The Book of the Dead” is telling: “My father is gone” (3). Although this refers to his physical disappearance, it also sets up the loss Ka is about to experience through her father’s confession. “The Book of the Dead” is the story of Ka losing her father. Her relationship to him, and to Haiti, has been based on an imagination that does not line up with his past, and so the loss of this imagined reality translates into the loss of her father. It is a complex loss, and we are never given an answer to what happens to Ka’s relationship with her father after this revelation, just as there is never a straight answer as to whether the Dew Breaker has really redeemed himself. But it is clear that the father she attempted to immortalize is gone. This raises questions about that “universal world of fathers,” and Gabrielle Fonteneau’s father – if the sculpture reminded Gabrielle of her father, and we know that the subject of the sculpture is not who he seemed, then this can and does bring into question all of the various fathers in the book, particularly when the information we receive about them is solely from their children. Ka’s relationship with her father, then, relates to the other depictions of fatherhood throughout The Dew Breaker in a number of ways, perhaps most notably, in that it begins with loss, a theme that exists almost perpetually in relation to fathers throughout the book.

In the final story of The Dew Breaker, Danticat quotes a revised version of the Lord’s Prayer from Papa Doc’s regime: “Our father who art in the national palace, hallowed be thy name. Thy will be done, in the capital, as it is in the provinces. Give us this day our new Haiti and forgive us our anti-patriotic thoughts, but do not forgive those anti-patriots who spit on our country and trespass against it…” (185). A few pages later, she notes that the president is “also known as the Renovator of the Fatherland” (189). Although significance of the revised version of the Lord’s Prayer is perhaps largely in giving the president the role of a god, within the context of this book, I find the way in which this also frames him as a father figure significant. Fathers in all of the stories are almost exclusively associated with loss and absence – whether physical or emotion, and whether by death or by choice – and the president as an authoritarian leader represents more of an excess of presence. Unlike the other fathers, it is his presence that causes suffering for his “children,” rather than his absence, at least during his rule. Both the president as father, and the Dew Breaker as father, also raise more questions of the possibility of redemption. The most present of the fathers throughout the book are both those who occupied the “hunter” space in the “hunter/prey” binary introduced in the beginning. And their hunting is what resulted in the “fatherless generation.” Is it right, then, that Ka’s father is present for her? Or is it fitting that she loses him just as he, and the presidential father for whom he worked, caused others to lose their fathers?

Works Cited

Danticat, Edwidge. The Dew Breaker. Vintage Books, 2004.

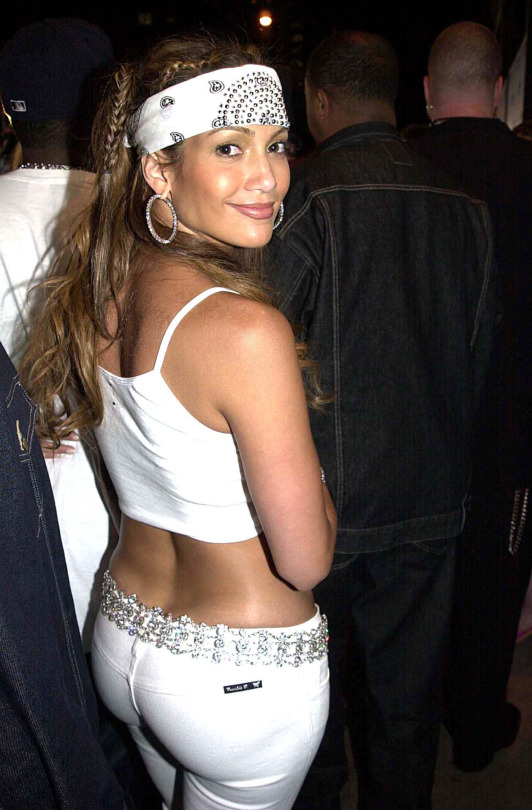

JLo’s Performative Defiance in Negrón-Muntaner’s BORICUA POP

Frances Negrón-Muntaner is a Puerto Rican filmmaker, writer and scholar. Negrón-Muntaner’s 2004 book Boricua Pop: Puerto Ricans and the Latinization of American Culture is a collection of critical essays that address issues of commodification of Puerto Rican difference in American culture.

Her Chapter 9, entitled, “Jennifer’s Butt: Valorizing the Puerto Rican Racialized Female Body” elaborates on the politics of racial representation with celebrities by doing a close reading of Jennifer Lopez’s career, more specifically, the contentious discourse surrounding her curvaceous rear. It is extremely informative how she ties values of capitalism to racial identification. The use of the word Latina to commercially include a wider audience of fandom is an important money making construct. Negrón-Muntaner writes, “In this marketing and audience-building trajectory ‘Latino’ here refers less to a cultural identity than to a specifically American national currency for economic and political deal making, a technology to demand and deliver emotions, votes, markets, and resources on the same level—and hopefully at an even steeper price—as other racialized minorities” (231). This is a commodified absorption of ethnic difference. But Jennifer Lopez is also addressing “a common experience of having a similar build, a body generally considered shameful by American standards of beauty and propriety” (232). Lopez uses her body as an innovative site to reimagine how Latinas and other minority groups are broadly racialized and represented as excessive (in food, sexual appetites, etc.). She is engaging in a ‘grotesque gesture’ of performance to combat the discourse of shame associated with her big butt (read: racial difference). She refuses to show shame, despite the cultural assumption that it is OK to question her “realness” and comment on her proportions. But Negrón-Muntaner is careful to recognize the restrictions of performative defiance under the “hostile cultural gaze” (235). She traces the backlash against Lopez as a diva, and the eventual recovery of her image based on re-branding herself through working out, dumping Sean Combs and staring in big box office roles that cast her as mostly ethnically ambiguous if not blatantly of different background (e.g.Italian). I was most struck by the tie between capitalism and racialized/sexual representation—and how performance can to some extent evade these categories but also needs to work within the system of commodification to re-brand what sells within the public.

I recommend this book to scholars interested in popular culture, race, gender and sexuality studies, specifically those related to Puerto Rico and its diaspora. The book also has chapters on West Side Story, Ricky Martin, and Holly Woodlawn, with interesting insights on Puerto Rican homosexuality in the United States. The language is very accessible, and could offer a compelling introduction to students just delving into these areas of study.

The whole book is available online as an eBook through OSU’s library: https://muse-jhu-edu.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/book/7707 (you can download each chapter individually–“Jennifer’s Butt” is Chapter 9).

Work Cited

Negrón-Muntaner, Frances. Boricua Pop: Puerto Ricans and the Latinization of American Culture. New York: New York University Press, 2004. Web.

To Buy or Not to Buy Fundraising Swag

For this last post, I would like to turn to a current topic that I can’t seem to work through: fundraising swag.

For this discussion I will turn to the Standing Rock Tribe and movement dedicated to saving helping the Standing Rock Tribe keep their land and homes and our environment. I personally find this the largest tragedy of our time, because not only are we repeating one of the most appalling events in this nation’s history—taking land by force with bigger weapons—but it is also an environmental calamity because if anything were to go wrong, it would make this plant less habitable… and it’s already a scary topic to consider.

So while this story is extra hard to ignore given the popularity of the topic on social media, what has caught my attention is the merchandise available for purchase; merchandise that says: “Stand with Standing Rock” or “Water is Life.” And while this at first seems like a wonderful holiday gift (because at least consumerism is being used for a noble cause), I am torn because it then seems that is in the goods we buy which is the thing that propels individuals toward solidarity.

In Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto (1848), he discusses the idea of exploitation of one social class by another. Marx writes, “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.” And while he explains that class ranking is embedded within human (civilized) history, he ultimately finds that modern class separation exists through “Modern industry” (14-15).

Returning to this idea of fundraising swag, where most or all proceeds go to a good cause, I can’t help but question if it is symbolic of the “oppressor and oppressed” relationship that remains a part of the “contending classes” as Marx suggests?

The swag exists because of the marginalized citizens and it allows other groups to participate and help in this struggle, but ultimately it is done through industry. Buying the Standing Rock shirts helps (yes!), but it is basically like purchasing the thing that they are trying to stand against—or maybe that is a bit of an exaggeration. I find that this is a slipper slope because on one hand I see this item for purchase for a good cause as juxtaposing what it signifies, but on the other hand it is bringing awareness to the situation and encouraging other classes or groups of people to participate in a good cause. Getting something for your donation is more appealing than just donating, so is it good or bad? But it also seems problematic because what if other sites pick up on this popular trend and sell the swag for profit and not for donations? Google “Standing Rock shirts” and this might already be the case…